The prototype of Nezha can be traced back to the “Nezha” in ancient Indian Buddhism. After his image was introduced into China, he was integrated with local Taoism and folk beliefs. Nezha also underwent many evolutions before he was finally finalized, forming the Nezha we know today.

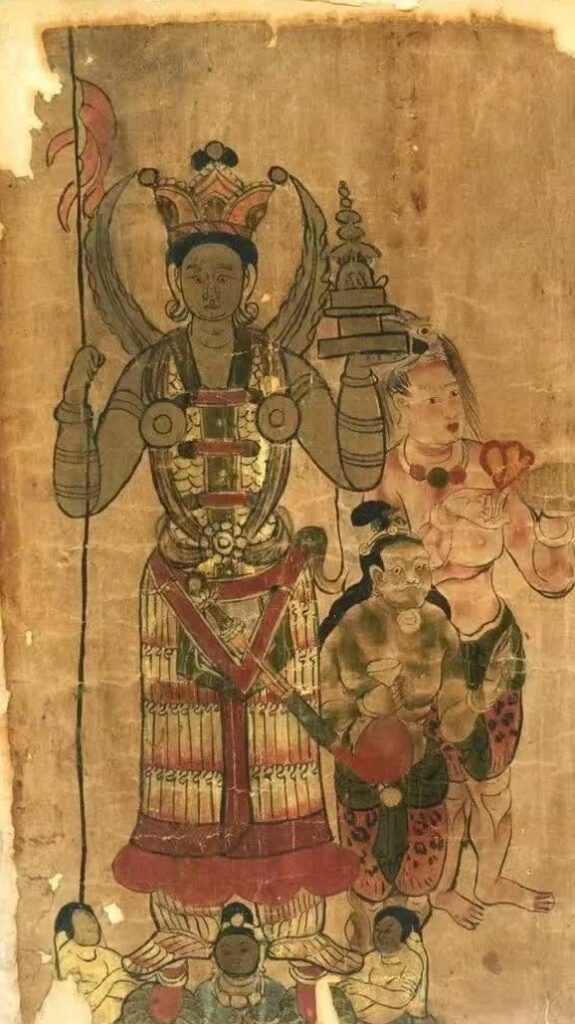

According to research, the “Praise of the Buddha’s Deeds” written by the ancient Indian Buddhist master Aśvaghoṣa is the earliest Buddhist scripture to mention “Nezha”: “The King of Vaisravana gave birth to Narajuva, and all the gods were delighted.” In the Buddhist scriptures, his “three heads and six arms” image is quite unique. He often appears in the image of a boy, protecting the Dharma with his father, with great supernatural powers, and subduing demons.

After the Tang Dynasty, the image of Nezha in Buddhism was combined with Chinese folk beliefs and evolved locally. Nezha was gradually incorporated into the Taoist system of gods and was revered as the “Marshal of the Central Altar”. During the Southern Song Dynasty, Li Jing evolved into the Northern King of Vaisravana. In the Southern Song Dynasty’s “Five Lamps Collection”, the story of Nezha “cutting flesh to return to his father” first appeared, which transformed him from a Buddhist guardian to a Taoist god and Taoist boy, and his image gradually took root in China.

In the Ming Dynasty, Nezha’s image gradually took shape. According to the Complete Collection of Gods of Three Religions, “Nezha was originally a Daluo immortal under the Jade Emperor, six feet tall, with a golden wheel on his head, three heads, nine eyes and eight arms… Because there were many demon kings in the world, the Jade Emperor ordered him to be born into the mortal world, so he was conceived by Madam Suzhi, the mother (wife) of Li Jing, the Pagoda-Bearing Heavenly King.” Elements such as Nezha’s rebellious character, his following of the Buddha, and his birth from a lotus flower were inherited by later generations.

Nezha’s portrait in the Qing edition of “Three Religions and Their Origins and Their Gods Collection” The reason why Nezha’s image is so well known is mainly due to the Ming Dynasty “Investiture of the Gods”. In this novel of gods and demons, Nezha’s typical image was finalized. After this “remodeling”, Nezha was fully integrated into the Chinese cultural context and became a mythological figure with distinct Chinese characteristics.

“Investiture of the Gods”, which is included in the Jiangsu Library Essence, comprehensively shaped Nezha’s image in the twelfth to fourteenth chapters: Nezha is a disciple of Taiyi Zhenren, a fairy of the Chan religion. He was originally the reincarnation of “Lingzhu” and was reborn as the third son of Li Jing, the general of Chentangguan. His mother is Madam Yin. Nezha was born as a meat ball with the magic weapons “Qiankun Circle” and “Huntian Ling”. He has great supernatural powers since he was a child. At the age of seven, he could call the wind and rain. He has extraordinary power and a rebellious character.

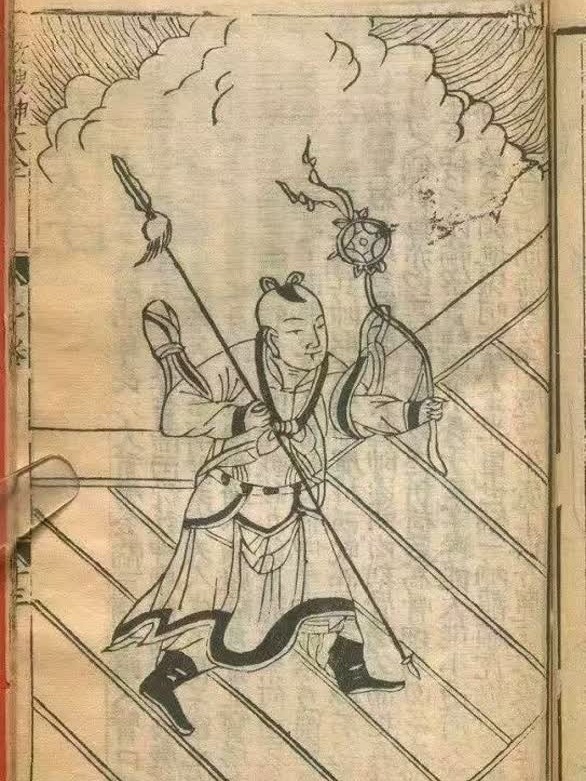

The Qing Dynasty ink painting compilation “The True Shape of the Investiture of the Gods” features a striking portrayal of Nezha, immortalizing the deity’s dynamic essence. The text chronicles the legendary tale of “Nezha’s Trouble in the Sea,” recounting how the young hero, while bathing in the Jiuwan River near the East China Sea, stirred the waters into chaos with his magical Hun Tian Ling. This act destabilized the Dragon Palace, provoking Ao Bing, the Dragon King’s third prince, to confront him. In the ensuing clash, Nezha slew Ao Bing and extracted his dragon tendon—a reckless act that ignited a celestial crisis.

Enraged by his son’s death, the Dragon King unleashed floods upon Chentangguan. Defiant yet honorable, Nezha proclaimed, “A man must bear the consequences of his own acts,” choosing self-sacrifice to spare his family and townsfolk. He returned his bones to his father and flesh to his mother, severing familial debts. Through Master Taiyi’s intervention, Nezha was resurrected in a lotus-formed body, reborn with heightened power.

Now a transcendent warrior, he joined Jiang Ziya’s campaign against the tyrannical King Zhou, emerging as a pivotal ally. As a vanguard, he triumphed over formidable foes like Zhang Guifang and the Demon Generals, cementing his battlefield prowess.

In The Investiture of the Gods, Nezha embodies a captivating paradox—youthful mischief fused with unyielding valor, ethical resolve, and rebellious spirit. Blending myth, morality, and heroism, his legacy transcends eras, inspiring countless adaptations in art, literature, and worship, solidifying his place as an enduring cultural icon.

The Ming-era Newly Engraved Complete Journey to the West, preserved in the Jiangsu Library, reimagines Nezha not through the lens of his tragic past but as a celestial enforcer of divine order. Here, he is depicted as the third son of Li Jing, the Pagoda-Bearing Heavenly King, embodying the might of the heavens with his three heads, six arms, and an arsenal of mystical weapons: the Fire Spear, Universe Circle, Chaos Ribbon, Wind-Fire Wheels, and Demon-Slaying Sword. Unlike his complex portrayal in Investiture of the Gods, Nezha in Journey to the West thrives as a battle-hardened general, famed for spearheading the purge of “ninety-six demonic lairs” and aiding Sun Wukong in vanquishing the Bull Demon King—a clash of titans that underscores their uneasy alliance.

Nezha’s character melds fierce resolve, formidable arcane prowess, and an eternally youthful vigor. His three-faced, multi-limbed form becomes a symbol of celestial authority, elevating the hierarchy of heavenly generals while infusing the pilgrimage narrative with Taoist mythos. Though secondary to Sun Wukong’s chaotic brilliance, Nezha’s disciplined ferocity provides a striking counterbalance, reflecting the Taoist duality of order and rebellion.

By weaving Nezha’s divine interventions into the fabric of Journey to the West, the Ming text amplifies the celestial bureaucracy’s role in the mortal realm, enriching the epic’s spiritual dimensions. His legacy—a blend of martial divinity and boyish exuberance—transcends the page, cementing his status as a timeless bridge between heavenly duty and earthly myth.